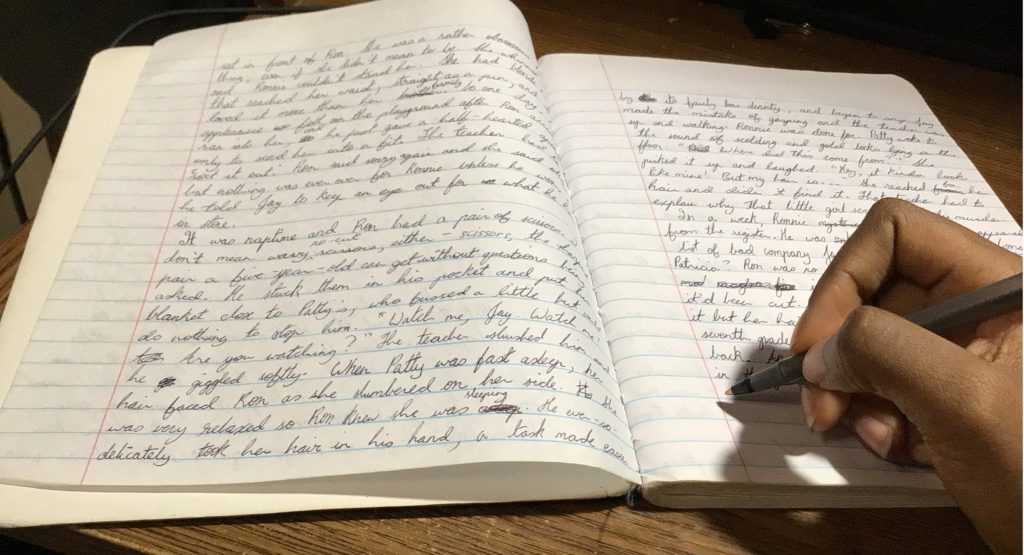

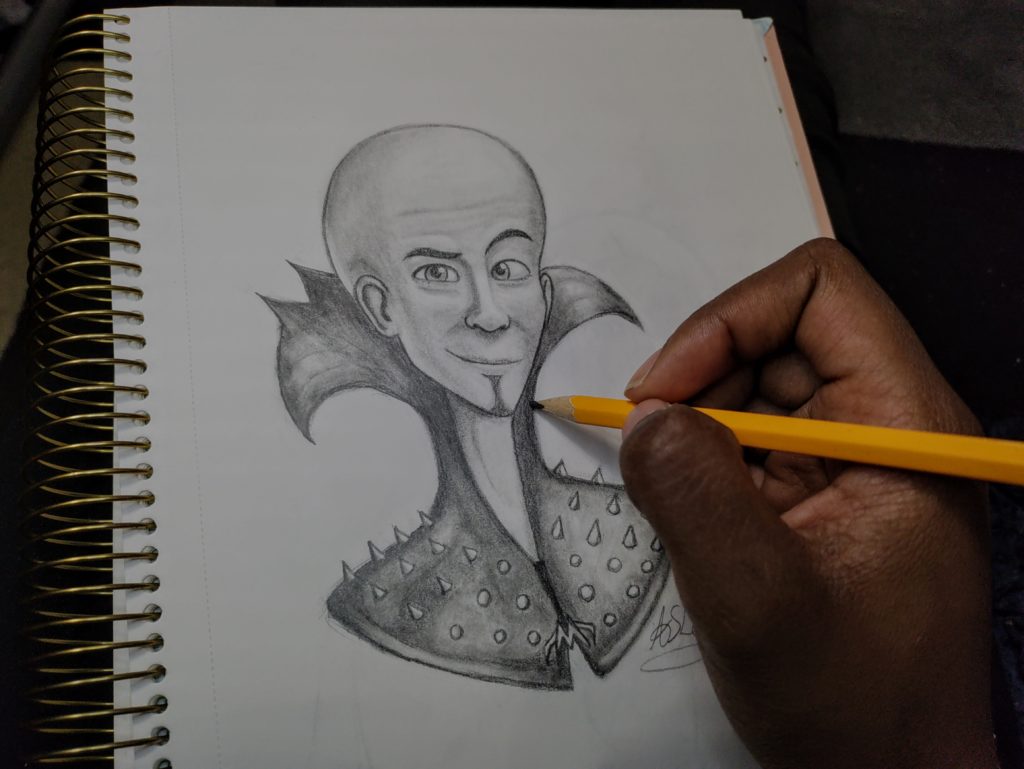

Pictured: Me with my sketchbook, plus my drawing of Megamind 😉

Full disclosure: I don’t intend to convince you that mediocrity is intrinsically a good thing. This is not a write-up about why it’s totally fine to slack off at work, or why you should be fine with and accept your dead-end job, or not turn in your assignments on time because doing ‘just enough’ when your potential is greater than that is actually a good thing. But what I am going to tell you is that it’s okay to not be good at things you enjoy. You may not be able to become a successful author if your writing fails to captivate people (although I’ll admit that some novels that have sold well never fail to baffle me), but this does not mean you should not write if getting a story out on the weekend makes the thought of next Monday a little more palatable. What this article is is a defense of being bad at your hobbies.

Mediocrity is something we’re societally discouraged from praising, as we’re instead supposed to strive for and lust after productivity and exceptionalism. When we talk about one’s work, obligations, educational pursuits, and so on and so forth, I see this as a fairly reasonable (if overzealous) perspective to have. And yet, as we claim that hobbies are good for the soul, pen and publish self-help books, sell new-age spiritualism and fad diets and bath bombs as remedies for a stressful life, one’s attempt to start any hobby seems inevitably built on the assumption that you’re striving for objective quality.

After all, if you’re good at it, it might even become profitable one day, right?

Phase 1: “Who cares if I’m bad at my hobby?”

During the transition from late prepubescence to early adolescence, I picked up a hobby independent of the creative writing I had recently been deemed to be talented at by the adults who familiarized themselves with my growing collection of poetry: I began drawing. From the beginning, visual art was something I knew I was not very good at — nonetheless, I found it comforting at a time where I was displeased with myself and the situation around me, and it was less mentally taxing than writing while working in tandem with it. I drew my characters, jotting down personality traits and story notes in the corners of the drawings.

My first ‘sketchbook’, which has been sitting on a shelf for a few years, was two composition books stapled together cover-to-cover and sheathed in fluorescent paper to mask the shoddy DIY nature of it and prevent the books from coming apart by accident. I used it throughout almost the entirety of 7th grade, and a few of the characters within have continued to be revamped and improved upon in the 6 years since their inception, continually aging with me from an antisocial and discontent 12-year-old to an introspective but moody 18-year-old.

In 8th grade and going into 9th grade, shocked that I was still doodling in the margins of notes and having since upgraded to a real sketchpad, I turned my smartphone into my first little animation studio and put my drawings in motion for the first time. Animating would take up my full attention for blocks of 4-12 hours at a time — specifically during vacations. Making quick clips with my characters and fan work of other established properties was my newest pastime, and at first, I had no concerns about the quality of the product: I would just be proud to finish them.

And then I watched people criticizing other small/hobbyist animators online, and I feared that my own animations were boring, repetitive, and stiff. This was, evidently, the beginning of the end (at least for now).

Phase 2: “Oh my God, am I actually bad at my hobby?”

From then on, my primary goal for animating seemed to no longer be stress relief or relaxation — these were only passive benefits, as my real goal was slugging away until I created the best thing I could make. The mendacity of amateur work was viewed only as something to be corrected, even though I was a hobbyist. It was not about enjoying my work at every stage so much as it was fighting for and dreaming of when it would be better.

Don’t appreciate the chrysalis in and of itself; just appreciate that it’s a sign that a butterfly will be here soon. The chrysalis is unpolished and ugly, indicative of poor craftsmanship by untrained hands. The work put into bringing it into existence does not make it good, and the embarrassment I feel from knowing that should, in theory, inspire me to work harder.

Spoiler alert: this mindset has effectively ruined one of my hobbies, and I’ve been unable to enjoy it to the same degree ever since. I have not completed an animation in two years, and I have several failed drafts since then I have not been able to keep the motivation to finish. My fear that my animations were inferior dredged up other concerns that my art is not up to par either, and this poisoned the safe space I used to go into when life was getting me down. I have not given up on it, but my ever-present daydreams and plans for what I could be animating have not materialized in quite a while.

So, what’s the moral of this long, rather melancholic story? Well, here’s where I defend mediocrity: whether young or old, whether you draw, paint, sew, write, take pictures, or whatever else gets you through a long day, you don’t need to be good at it. And maybe you already knew that, at least objectively, but if you’re anything like me and are prone to holding yourself to a standard you can’t meet, here’s your friendly reminder that you don’t have to be good at the things you enjoy doing if you do them just to make yourself happy.

If your primary goal isn’t improvement, who cares if you’ll stagnate a bit if you just paint the same thing every time you sit by your easel? What if you don’t want to branch out or stop playing your favorite song that only has four chords? People crack jokes about the ‘Wonderwall guy’ who just picked up a guitar and never gets past campfire chords, but if you don’t mind staying a beginner, I say rock on! Just play by yourself or with people who support you enjoying yourself.

What learning to let go and embrace mediocrity does for me is that it allows me to take pride in the crude middle stages. When I started teaching myself guitar, I let myself play whatever I wanted for as long as I wanted, which often meant only a few easy songs, and moved on whenever it felt right. I may not have gotten as far as Joe down the block did in the three years since I started, but I still actively enjoy it, and I picked up new techniques like fingerstyle when it felt right because I didn’t see my first-month shoddy renditions of Red Hot Chili Pepper songs as ugly — I saw them as fun.

So hobby on, my friends. You deserve a space where you don’t have to conform to anyone else’s standards. You deserve something that you don’t have to be graded on. The world’s already good enough at trying to turn everything about you into a number, but don’t let it convince you that your hobbies are less meaningful if you’re not trying to do them ‘right’.

— Dee